Sri Lanka’s crisis follows similar pattern as Arab Spring, say analysts

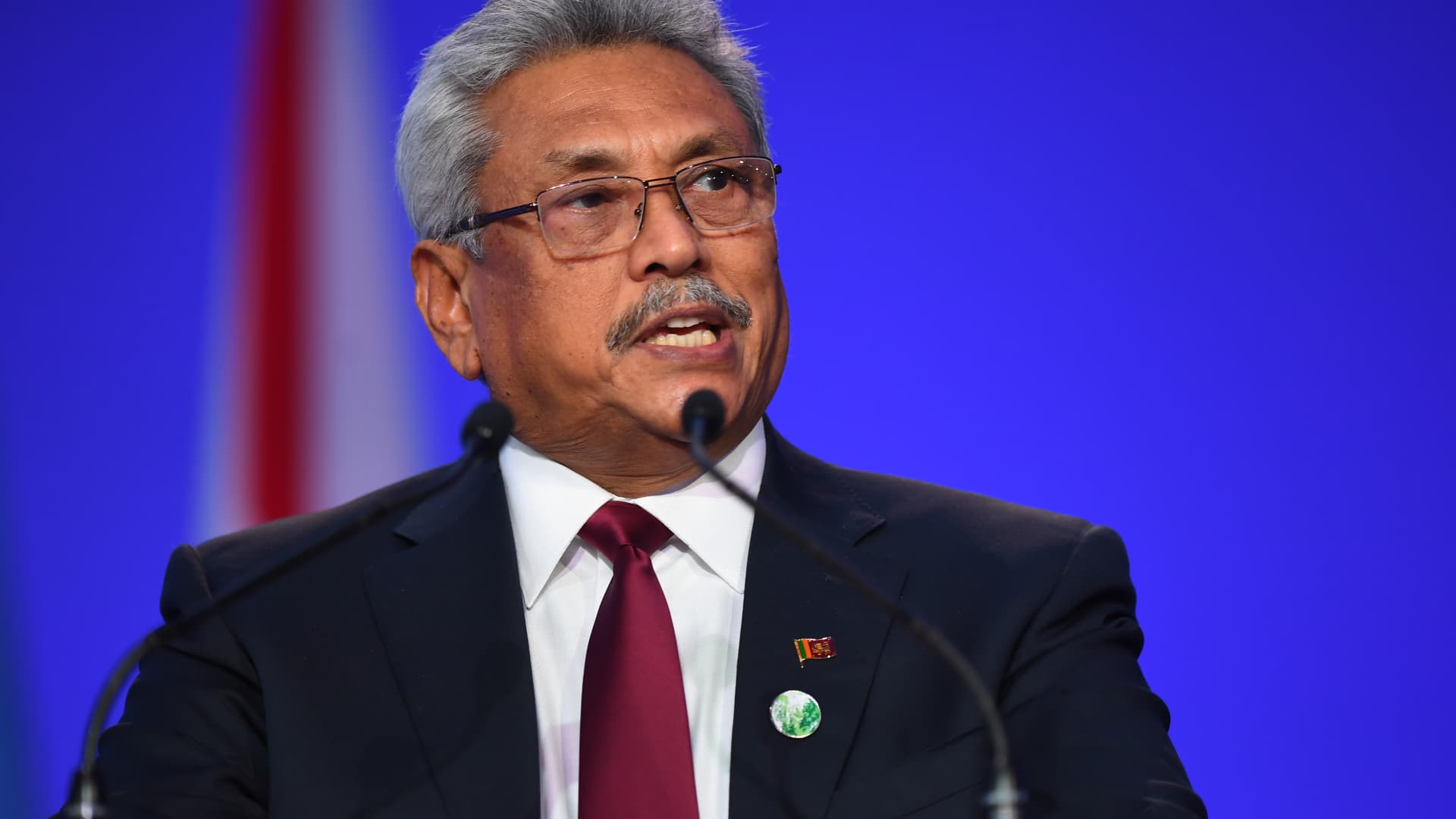

Thousands of Sri Lankans took to the streets on Monday calling for the ouster of Sri Lankan President Gotabaya Rajapaksa seen here on November 1, 2021 in Glasgow, United Kingdom.

Andy Buchanan | Pool | Getty Images

“Gotta go, Gotabaya,” chanted thousands of people who came out on the streets of Sri Lanka to demand the ouster of President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, defying a state of emergency in what analysts called the Sri Lankan version of the Arab Spring. The president later revoked the state of emergency, which had not stopped the demonstrations.

“It’s the Arab Spring in Sri Lanka. It’s a perfect match with the pattern of an Arab Spring: a people’s uprising to end authoritarian rule, economic mismanagement and family rule, and install democracy,” Asanga Abeyagoonasekera, senior fellow at Millennium Project in Washington, told CNBC.

The Sri Lankan High Commission in Singapore did not respond to a CNBC request for comment.

The Arab Spring refers to a series of protests that began with the self-immolation of a vendor in Tunisia in 2010 and spread across several countries in the Arab world such as Egypt, Libya, and Syria against authoritarianism, corruption, and poverty. As many as four autocrats, including Egypt’s Hosni Mubarak, were ousted during the Arab Spring.

The powerful Rajapaksa clan has ruled Sri Lanka for decades and came back, after a brief spell out of power, in 2019 when Gotabaya was elected president. Although troubled by corruption allegations, the current dissatisfaction stems from economic mismanagement. Gotabaya was once popular for ending a decades-long civil war in 2009, with a bloody bombing campaign against Tamil separatists.

At least 41 Sri Lankan lawmakers walked out of the ruling coalition, leaving the Rajapaksa government in a minority in Parliament. On the same day, the government was dealt another blow when finance minister Ali Sabry resigned just a day after his appointment.

“I believe I have always acted in the best interests of the country,” Sabry said in a statement. He said “fresh, proactive and unconventional steps” were needed to solve the country’s problems.

This country is no longer going to tolerate any Rajapaksas in government.

Harsha de Silva

Member of Parliament, Sri Lanka

Like the crisis in Sri Lanka, the Arab Spring was also triggered by economic stagnation and corruption in Tunisia, said Chulanee Attanayake, research fellow at the Institute of South Asian Studies at the National University of Singapore.

“Sri Lanka is also witnessing anti-government protests in response to an economic downturn, rising inflation and shortage of essential goods. Similar slogans as during the Arab Spring are also being used,” he said.

An association of medical professionals in Sri Lanka has declared a health emergency over a shortage of medicine and equipment, local media reported.

But Fung Siu, principal economist for Asia with the Economic Intelligence Unit, a think tank, disagreed with the Arab Spring parallel.

“Triggers for the Arab Spring were years in the making, while discontent in Sri Lanka can be traced back to the onset of the pandemic and bad policy choices,” she said.

Cabinet shuffles as public outrage grows

Sri Lanka’s cabinet and central bank governor quit on Monday in the face of mounting public anger and mass protests over rising food and fuel prices. Sri Lanka has sought IMF bailouts 16 times in the past 56 years, second only to debt-ridden Pakistan.

Fung said a fresh IMF loan could help but a period of fiscal austerity would follow.

“Although such efforts will help to address imbalances, higher taxes will probably stoke anti-government sentiment further,” she said.

Faith in the government has also plunged, Attanayake said, adding that disappointment has grown since the country’s independence.

“The events happening right now show the public’s lack of trust in the political leadership, and their impatience, frustration, and disappointment. They will not tolerate the missteps, mishandling and mistakes anymore,” he said.

The 26 cabinet ministers who resigned include Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa’s son, Namal, who tweeted that he hoped it would help the president and prime minister’s “decision to establish stability for the people and the government.”

Sri Lankan Member of Parliament and opposition leader Harsha de Silva said only a fresh election could present a solution.

“The reshuffle is only temporary. They have appointed only four members to the cabinet… I don’t think they have any credibility left to stay on. So unless we are able to build back confidence, I do not know how to get this country’s economy back on track. The only way to do that is to have a fresh mandate for a new set of people,” de Silva said on CNBC’s “Squawk Box Asia.”

Still, the MP said it was too early to tell if the president would be forced to step down.

“This pressure started building up only 48 hours ago,” he said. “Things are moving fast today, and Parliament will meet after two weeks. And then we can see if the government still holds the majority.”

Asked if he was open to joining a national unity government, de Silva signaled assent. But, he continued: “The problem, however, is that this country is no longer going to tolerate any Rajapaksas in government. So it is not going to be possible to work in a government with the Rajapaksas.”