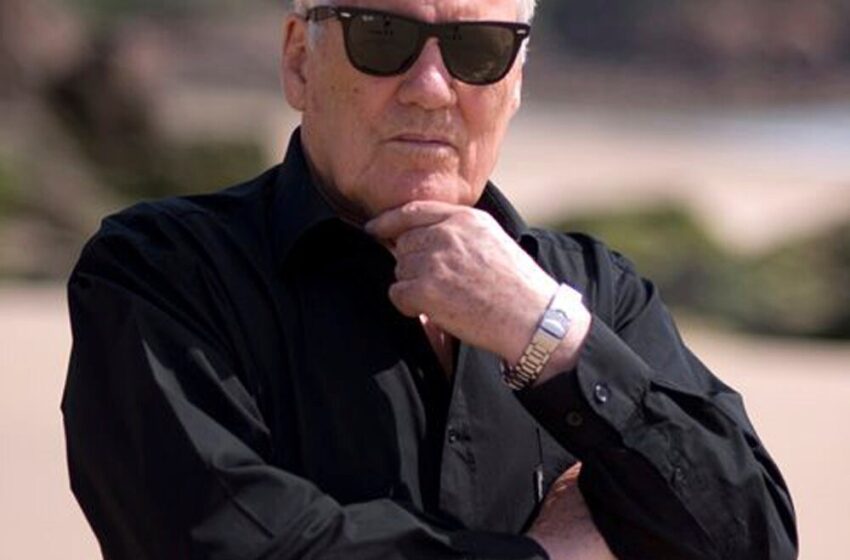

Jack Higgins, best-selling author of ‘The Eagle Has Landed,’ dies at 92

Charlie Redmayne, chief executive of his publisher HarperCollins UK, announced the death but did not provide a cause. Mr. Higgins — the best known of the many noms de plume of Henry Patterson — had a nervous system ailment that in recent years interfered with his writing.

A former soldier turned teacher, Mr. Higgins began writing in the evenings under his birth name and over the years used Hugh Marlowe, Martin Fallon and James Graham because he churned out so many novels so fast that no one publisher could print them all in any given year.

“The Eagle Has Landed,” published in 1975, made Jack Higgins a global commodity (Higgins was his mother’s maiden name). One would be hard-pressed to find an airport bookshop anywhere in the world, even in non-English-speaking countries, that doesn’t display a Higgins novel on its shelves. In a statement, Redmayne said that Mr. Higgins was known around the publishing house as “The Legend.”

For all its adventurism, “The Eagle Has Landed” also demonstrated Mr. Higgins’s ability to remind his readers of moral complexity and cast doubt on who are heroes or villains in individual circumstance — in this case, war.

The book is set in September 1943 when Germany’s war effort, including Hitler’s original intention of invading Britain, is faltering. A group of disguised German paratroopers, aided by an anti-British sympathizer from the Irish Republican Army (IRA), is tasked with trying to kidnap or kill Churchill during his visit to a village in eastern England.

When Mr. Higgins wrote his first draft, he said an executive at Collins Publishers was first confused by the title (“he said it sounded like a bird book”). The executive then grew hesitant because the plot seemed too sympathetic toward the German protagonists, showing them as honorable men on a mission they considered justified, and also glorifying the IRA’s anti-British stand. The author, raised for part of his youth amid the sectarian conflicts of Northern Ireland, was keen on exploring the moral and psychological ambiguity of his characters.

But his editor at the time said he viewed it as an “instant classic” and was fully validated after Holt, Rinehart and Winston brought it out in the United States to resounding commercial success. “The Americans had to reprint it once a month for a year to meet demand,” he told Reuters.

“The Eagle Has Landed” went on to sell 50 million books in more than 50 languages and was turned into a 1976 movie starring Michael Caine, Donald Sutherland, Robert Duvall and Jenny Agutter.

Mr. Higgins reportedly received seven-figure advances for his later work, most of which were impervious to middling reviews. “Too much depends upon likely coincidence,” thriller and mystery reviewer Newgate Callendar wrote in the New York Times of Mr. Higgins’s “A Season in Hell” (1989). “But Mr. Higgins is a real pro, and he keeps things moving so fast the reader is apt to forget and forgive.”

Such was also the case with his last novel, “The Midnight Bell” (2016). Set in Northern Ireland, its plot involves a former IRA hit man, Sean Dillon, the subject of many of his earlier books, as well as an al-Qaeda terrorist leader, the White House, the CIA, the British government and several subplots. Many readers found the story hard to follow, but it — like so many before it — wound up on the bestseller lists.

Henry Patterson was born in Newcastle upon Tyne, in northeastern England, on July 27, 1929. His father was a shipyard worker turned racetrack bookmaker from Scotland, while his mother was from Belfast in Northern Ireland.

He was a toddler when his father walked out on the family, and he and his mother moved to her family home in Belfast. Conflict was simmering between pro-British Protestants and Catholics who wanted a united island of Ireland; this was long before the violent “Troubles” that erupted in 1969. Young Harry, a Protestant, witnessed bombings as well as a gun attack on the streetcar he was riding to school (his mother pulled him to the floor to protect him).

He also recalled that his great uncle, whose name was Jack Higgins, had a drawer full of hand guns and would load one, put it in his overcoat and casually tilt his trilby hat in front of the hall mirror before taking young Harry for a walk along Belfast’s Shankill Road.

When he was 13, his mother remarried and took him to Leeds, England, where he got into trouble by throwing snowballs at his new school’s tower clock. The headmaster told him he would “amount to nothing” and flogged him with a cane. “I was in agony, of course,” he told the Yorkshire Evening Post. “He didn’t just give me six, he gave me nine strokes. But I was buggered if I’d blubber [cry] for him.”

Leaving school at 15 to help support his mother, he took on menial jobs helping erect tents for traveling circuses and working as a fare collector on local street tramcars. For his compulsory national military service in 1947, he found himself in the British army’s Household Cavalry, a historic combination of regiments, although best known now for its formal role as protectors of the monarch. Mr. Higgins gained awards as a sharpshooter.

Military tests showed him that he, in fact, had an exceptional IQ, and he was determined to return to school. He received a degree in sociology from the London School of Economics (LSE) and became a schoolteacher. Meanwhile, he was given a battered copy of the F. Scott Fitzgerald masterpiece “The Great Gatsby” and was inspired to try writing.

His first book, “Sad Wind From the Sea” (1959), an adventure story set in China, was published under his given name for a 75-pound advance. His school pupils were impressed, and, despite modest sales, he was emboldened to continue.

He said that his 1966 novel “A Candle for the Dead,” written as Hugh Marlowe and about an escaped IRA explosives expert, also had underwhelming sales but that the 1967 film version, “The Violent Enemy,” brought in royalties three times his teaching salary. He decided to give up teaching and write full time.

His 1971 novel “The Wrath of God,” about a band of revolutionaries in South America and written as James Graham, brought in even more royalties with a 1972 film starring Robert Mitchum. Later screen adaptations of his work included “A Prayer for the Dying,” which was turned into a 1987 film starring Mickey Rourke as an Irish nationalist.

Mr. Higgins’s first marriage, to Amy Hewitt, a fellow LSE student, ended in divorce. In 1985, he married Denise Palmer, a former literary agent. In addition to his wife, survivors include four children from his first marriage. His daughter Sarah Patterson is author of a young-romance novel set against a World War II backdrop, “The Distant Summer” (1976).

Like many Britons who had just become wealthy, Mr. Higgins fled England after the British government raised the upper rate of income tax to more than 80 percent in the late 1970s. He settled on the island of Jersey, which is part of Britain but has lenient offshore tax status. He lived there for the rest of his life, in a mansion he described as “just like Monte Carlo,” writing until the wee hours of the morning before a glass of champagne, a bacon sandwich and bed.

In a 2010 interview with the Guardian, he said: “Yes, it’s been good. I’ve had the chance to do it all. The car, the driver, Beverly Hills, MGM, the movies, the Carson show, Larry King, hanging out with Richard Burton, being waited on by a dwarf in a green jacket in the Polo Lounge … the Hollywood dream and the Hollywood weirdness all happened. My son thought it was all a load of pretentious rubbish. He was right, but I thought I’d just enjoy it anyway.”