Attacks on civilians have spurred Ukrainians to join war effort against Russia — in any way they can

Tears welled up in Nastia Estomina’s eyes, in spite of a forced smile for the benefit of her young children, every time she thought of the difficult journey fleeing her home in Kharkiv, in eastern Ukraine.

While still there, they were under constant threat of shelling, with fighter planes flying so low at times Estomina could pick out the expression on the pilots’ faces.

Holding in the memories of life in Kharkiv before the war for the sake of calming her children is difficult, she told CBC News.

“You’re trying to be strong and hold in the emotions, but when you start to think about it, you ache to go back home,” Estomina said.

This isn’t the first time the 26-year-old has been forced from her home. In 2014, Estomina escaped from Sloviansk, in the Donetsk region of eastern Ukraine, after pro-Russian separatists moved into that strategic city.

Having now left Kharkiv, Estomina is intent on crossing into Poland with her two young children and her younger brother.

Sitting in a temporary shelter set up in the central train station in Lviv, a mere 70 kilometres from the border with Poland, Estomina is trying at once to soothe her five-month-old baby and keep an eye on her rambunctious two-year-old daughter.

“The children don’t understand, but we understand everything,” Estomina, 26, continued, wiping her eyes and describing her constant anxiety. “We don’t know where we are going, we’re just going, at least to where there are no sirens.”

Hovering nearby, ready to help, is trauma psychologist Olena Vorona. She volunteers here twice a week, and the need is even more acute now that the war in Ukraine is in its seventh week.

“They’ve lived through so much trauma, far more than the people we saw in the first few weeks,” Vorona told CBC News, specifying that often, a psychological reaction to the trauma of daily bombings and shelling can be delayed. “Someone can live through it calmly and they hold the emotions inside and the effects will be seen months later.”

Vorona is one of thousands of Ukrainians who are devoting their time and doing whatever they can to help support the country’s defence against the Russian invasion, including helping to send aid to those most in need, in the parts of the country in the east and the south hit hardest by the fighting.

Many volunteers report feeling even more determined to help out at all hours after devastating images in recent weeks emerged of civilians seemingly targeted by Russian attacks, which Ukrainian officials deem to be war crimes.

The Kremlin has denied the accusations.

‘There’s nothing else for me to do’

At a sprawling warehouse in the Lviv region, boxes upon boxes are piled up and stacked alongside pallets with everything from canned food to clothes to protective gear to medical supplies — much of it donated by countries around the world and entering Ukraine through nearby Poland.

Stella Pavlenko, 55, picked her way among the boxes, finding order in the chaos and relentlessly sorting supplies.

WATCH | Ukrainian volunteers pitch in to help with the war effort:

Residents across Ukraine are rallying together to help fight off Russia’s invasion, growing more motivated as more reports of war crimes are uncovered each day. 2:43

She is a dentist by trade, but as soon as the war broke out, Pavlenko closed her practice in order to spend every day helping at the warehouse.

“There’s nothing else for me to do. I’m more useful here for all of Ukraine, all the people,” she said.

“I feel that I’m doing a tiny piece for our country, for our people to feel some ease in places that aren’t easy,” Pavlenko said, adding that there are already enough dentists in the world. “They will cope without me.”

Her unstoppable energy is matched by her fellow volunteers, who are all giving their time to the cause. Even the warehouse space has been donated.

‘It’s very important for me’

Medical student Vladyslav Melnyk is one month away from graduation, but he now uses his medical expertise to sift through pills and surgical supplies, to prepare them to be distributed to places like Zaporizhzhia, the closest safe city to the southern port of Mariupol, which has been besieged for weeks and is in desperate need of supplies.

The list of destinations for the goods is long, and includes Kharkiv, near the Russian border; Chernihiv to the north of the capital, Kyiv, and a city that was encircled by Russian troops for several weeks; and Mykolaiv and Odesa in the south.

“It’s very important for me,” the 23-year-old Melnyk said, when asked why he volunteers every day. “You can see the massacre in Bucha, in Irpin, in other cities of Ukraine and it’s … very hard,” he said, with emotion in his voice.

“Here we try to give to our country all that we can.”

Much of the activity in the warehouse is overseen by Ostap Barannik. One of several co-ordinators, he moved from Kyiv to Lviv right before Russian tanks and troops invaded.

After his employer, Deloitte, paused operations in Ukraine, and with his family safely out of the country, Barannik had plenty of time to devote to his new full-time job of volunteering.

He’s convinced the shocking images out of Bucha and other parts of the country, where civilians were seemingly the main target for Russian forces, have served to strengthen the resolve of thousands of volunteers across the country.

“We are staying later [in the day] and trying to do more, just to make sure that we are helping more,” Barannik said.

‘This is my impact’

Others are using their fame and popularity to raise funds.

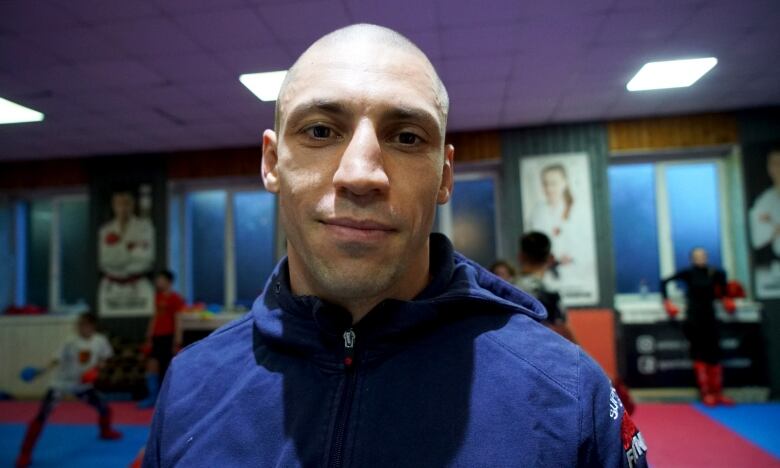

Stanislav Horuna, who won a bronze medal at the 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games in karate kumite, not only joined the all-volunteer Ukrainian Territorial Defence Forces when the war broke out, but also put his Olympic medal up for auction.

“It’s a piece of metal … but actually it symbolizes a lot,” Horuna told CBC News, right before a training session at his karate school in Lviv.

“It symbolizes all the work I’ve done to get to the Olympic podium and it symbolizes every victory on my way to the Olympic Games.”

Even so, Horuna didn’t hesitate to sell the “priceless” medal he had been aspiring to for more than 19 years while working out in the dojo karate hall, perfecting his martial arts skills.

“It’s a question of priorities, and now Ukraine is much more important for me than my personal interests,” the athlete said, adding that the money could be used to buy weapons or bulletproof vests for those in the line of fire.

“It can save somebody’s life.”

A few days before the bidding window closed, the medal was going for $11,000 US, which Horuna called “quite a good price for a piece of metal.” In the end, the winning bid was for $20,500.

“This is my impact,” Horuna said, “my small contribution to our victory.”